Multiple “Popeye” movies are sailing to cinema, TV and video-game screens as the property’s foundation copyright expires. Expect this to be a trend as intellectual property (IP) created during the early “talking pictures” days get aged out of legal protection.

Independent film companies are promoting “Popeye the Slayer Man” and “Shiver Me Timbers” (a signature Popeye phrase). The foundation Popeye property launched in 1929 (on the cusp of cinema’s “talkie” era as silent films faded). Copyright extends in most cases 95 years, so late 1920s properties now move into what is called the “public domain,” meaning free for anyone to exploit. The title, characters, plot and other signature elements of the expired-copyright property are already familiar to audiences, which makes the marketing task easier given familiar elements, and all without cost to the new production.

Other examples of recently expired copyrights are 1928’s “Steamboat Willie,” which was the first incarnation of Walt Disney’s Mickey Mouse character (the later versions of Mickey Mouse are still in copyright), author Ernest Hemingway’s novel “The Sun Also Rises,” and a raft of Jazz Era 1920s music. In several years, the expirations will roll into IP created in 1930s.

A Deadline.com trade newspaper article by Andreas Wiseman finds a handful of “Popeye” film/TV projects moving forward:

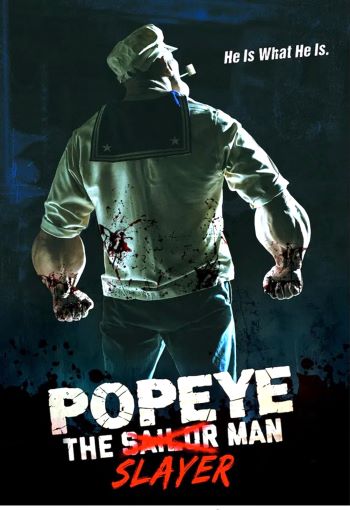

* Most advanced seems to be “Popeye the Slayer Man” that is a co-production between Salem House Films, Millman Productions, Ron Lee Productions, and Otsego Media. They say it’ll hit cinema screens next year.

* United Kingdom-based Alpake Entertainment began selling “Shiver Me Timbers” to distributors at the American Film Market a few weeks ago.

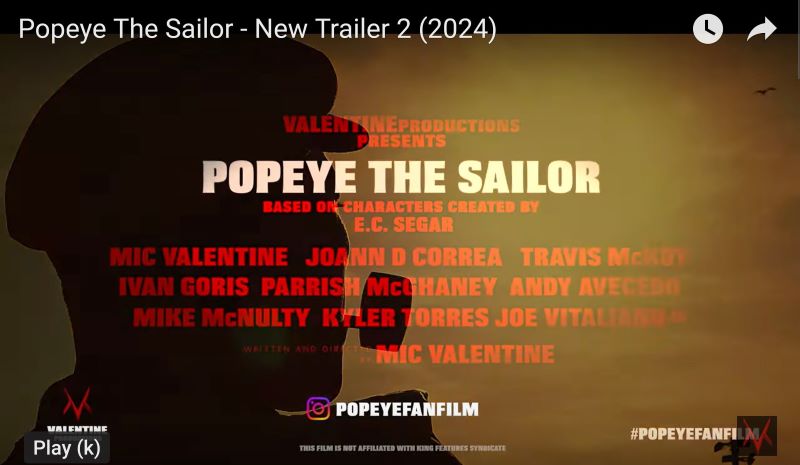

* Long gestating “Popeye the Sailor” (image at top of post is screen grab of credits) comes from Valentine Productions.

* Chernin Entertainment (the recent “Planet of Apes” movies) and King Features, which owns the now expired comics copyright, have been developing a “Popeye” movie.

The top three are from independents that presumably find it attractive to be able to use famed IP without having to pay. The YouTube trailer for “Popeye the Sailor” describes its movie as “a no budget, action, adventure fan film.” Indies veer to horror and humor because those genres are inexpensive, and don’t require pricey acting talent.

Fans get into the act too creating some polished film trailers placing stars Dwayne Johnson and Will Smith in fictional “Popeye” movie projects. These are online deep fakes.

Also, expect that with so many “Popeye” film/TV projects percolating, the later ones may be abandoned, since any first wave hitting screens can be expected to satisfy audience appetite. Also, audiences will be confused about late comers.

“When two or more films with in the same genre or with similar themes are poised to premiere around the same time, distributors scramble to be the first to hit screens,” says “Marketing to Moviegoers: Third Edition,” the academic/business book. “That’s because history shows the first film to open usually does best.”

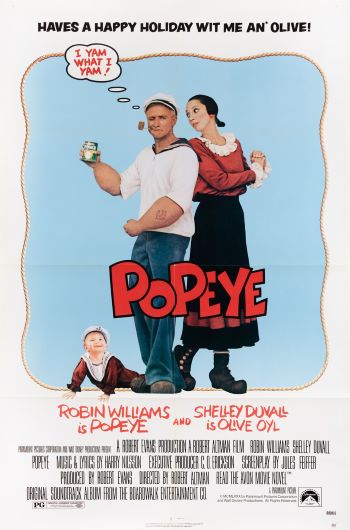

Another deterrent is that 1980 big-budget “Popeye” starring Robin Williams bombed for Paramount Pictures. Audiences found it difficult to understand Williams babbling in a sailor dialect.

Despite lack of copyright protections, some creative franchises get corralled by major Hollywood studios. A case in point is that Universal Pictures dominates the horror genre with a slew of copyrighted movies based on public-domain properties. Its Frankenstein movies are based on a novel published way back in 1818. Universal dominates horror by sheer weight of output, which deters others.

Beloved children’s story property Winnie the Pooh entered the public domain in 2022, and a UK producer made a slasher horror movie “Winnie the Pooh: Blood and Honey.” Despite that, Disney still holds copyrights on its extensive catalog of wholesome “Pooh” TV programs and movies, though in time those too will transition into the public domain. The book “The Wizard of Oz” was published in 1900, and the derivative “Wicked” stage play (now a movie too) did not launch until the foundational “Oz” property was in the public domain. A 2023 stage play musical based on the novel “The Great Gatsby” is likewise royalty free because the F. Scott Fitzgerald foundation book moved into the public domain two years earlier.

Larger players such as major studios want moats around properties they pickup to deter copycats of their big-budget movies. Big players also want to protect exclusivity for ancillary rights such as movie licensed merchandise. Though new works based on public-domain IP will get copyright protection for the entire movie, they lack an iron grip on spinoffs, licensed merchandise and other collateral exploitation.

For all the adaptations, the foundation rights are for the taking with public domain properties, but creations are legally obliged to steer clear of infringing on existing copyrighted movies. For instance, title treatments including color-scheme should be different to avoid confusing consumers, not copy later embellishments, not copy another property’s logo and maintain other points of separation from existing copyrighted content based on the same intellectual property. It’s complicated because modern incarnations can be true to the source material, or use source material as foundation for modern updates. For “Pooh: Blood and Honey,” there’s little chance of consumer confusion with the wholesome Disney versions.

In the broader film ecosystem, not only are foundation intellectual property up-for-grabs, but the movies themselves can be hitting the 95-year threshold (like the original “Steamboat Willie”). Copyright is legal protection of a creative work in its entirety. Copyright laws allow for excerpting for critical commentary (like film reviews), parody, education and other limited specified uses.

Works in their entirety get copyright protection, but not elements, such as film names. To avoid properties colliding, Hollywood’s major-studio trade group the Motion Picture Assn. operates a film title registry bureau, in which participation is voluntary. “Usually, a film company has done a full copyright search before attempting to register a name with the bureau,” according to “Marketing to Moviegoers: Third Edition”. “Film companies have claims on 120,000 different film names in MPA’s registry.”

As for outsiders trying to cash in on big film franchises, a notable interloper has been Italian film/TV outfit Mondo TV. Over the years, its animated “Simba: The King Lion,” “The Legend of Snow White,” “The Legend of Titanic,” “Jurassic Cubs” and others played on screens around the same time as heavily promoted major Hollywood films with similar themes and titles. The fence climbers grabbed some halo from the major properties. While amusing, Mondo’s me-too projects have not been particularly successful.

Related content:

Leave a Reply