Over the years, campaigns seeking Oscar awards aimed at Hollywood insiders have prayed to the Academy Award gods from the Alamo fortress and hosted a pop-up street stand in Hollywood hosted by a celebrated filmmaker who chatted up passers-by. And an actress personally wrote letters to every Academy Awards voter that she could find.

A Hollywood Reporter feature story by Scott Feinberg about a current controversy also recounts these past excesses in awards marketing (see the second half of article in Related Content). In the current controversy, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts & Science (AMPAS), which confers Oscars, gave a slap on the wrist to little-known British actress Andrea Riseborough, who snagged a Best Supporting Actress nomination for little-seen indie film “To Leslie.” AMPAS investigated and determined no major violation of its campaigning rules … but some minor infractions on social media campaigning were uncovered (Riseborough’s nomination stands … for major infractions, nominations or wins can be rescinded).

The current controversy pales in comparison to over-the-top campaigning years ago. “‘For your consideration” [awards] ads in trade papers like the Hollywood Reporter and Variety, which have always been read by a sizable portion of the Academy’s membership, date back to “Ah, Wilderness” in 1935. For the record, that film received zero Oscar nominations,” writes Feinberg in THR.

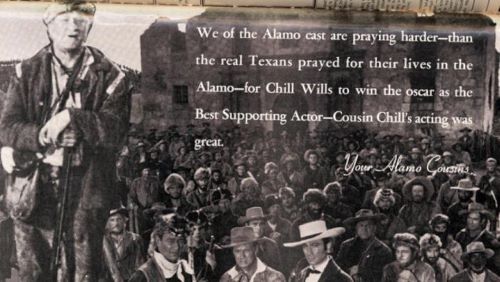

In the 1960-61 season, famed character actor Chill Wills pushed for supporting actor for his performance in historical epic “The Alamo” starring John Wayne. Wills received an Academy Award nomination and then in pursuit of the actual Oscar launched what THR characterized as a “series of unbelievably over-the-top ads, including one ostensibly written by Wills’ ‘Alamo Cousins’ claiming that they were ‘praying harder than the real Texans prayed for their lives in the Alamo for Chill Wills to win the Oscar.’ ” Get that? That’s supposedly harder than the real Alamo fortress defenders in 1836 when they knew they would likely be killed.

Comedian Groucho Marx stepped up next with a satirical trade advertisement in response to Wills that he was happy for the Alamo’s praying cousins but Marx said that he voted for Sal Mineo (neither would ultimately win the Oscar in question).

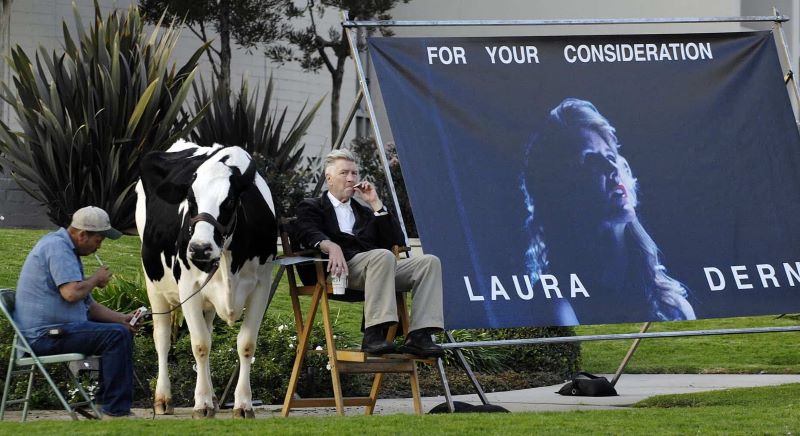

Another time, celebrated film director David Lynch personally manned a streetside display in 2006 to campaign for actress Laura Dern in his movie “Inland Empire” when the film’s distributor couldn’t afford an awards campaign. Lynch “happily chatted and posed for photos with anyone who cared to visit,” says the THR article. For some reason, a live cow was part of the street-side ensemble. The quirky Lynch ploy was for naught because Dern did not receive a nomination.

In 1987, actress Sally Kirkland wrote a personal letter to all relevant Academy voters asking that they consider her lead acting for an Oscar in “Anna.” Again, the distributor didn’t have funds for a proper awards campaign. Kirkland landed an Oscar nomination (but didn’t win); her efforts did bag other awards.

Oscar-organizer AMPAS “puts limits on overt campaigning — which are enforced with its members — in an effort to keep its awards process dignified,” says the third edition of book “Marketing to Moviegoers.” “Those rules are tweaked annually. … The Oscar campaign season generates hundreds of millions of dollars in economic activity, when including other awards that get spillover, advertising on awards telecasts, business-to-business advertising, parties, screenings, travel, and management overhead, such as executive salaries.”

Credible Oscar campaigns cost from $100,000 to $5 million — the larger efforts pile on expensive advertising, including local spot TV commercials in Los Angeles and New York where voters are concentrated. A more moderate paid-advertising cost is trade media advertising, which awards voters consume for business information. An example of trade advertising is the two-page magazine spread for “Avatar: The Way of Water” pictured at top.

Conventional awards advertising is dignified and is usually paid for by Hollywood companies, including marketing that is promoting specific talent and not the movie itself. The previously cited examples mounted in the past by talent stand out, such as Alamo cousins praying, because of their gaudy razzmataz and carnival-barker qualities.

Benefits to films vary. For talent, an Oscar win means salaries jump sharply in the future as producers seek figures who are promotable as “Oscar winners” or even Oscar nominated. Movies get a lift only from major awards, especially if those movies haven’t yet rolled up sizeable boxoffice.

In the Oscars’ earliest days, bloc voting by studios rolled up impressive hauls wins because of talent under contract. As the THR article says, “Joan Crawford famously declared, ‘You’d have to be a ninny to vote against the studio that has your contract and produces your pictures.’ ”

The bloc voting was most evidenced when MGM reigned over Hollywood in the 1930s and 1940s. The studio system dissolved in the 1950s, and bloc voting disappeared as talent increasingly moved around, with no single employer.

Related content:

Leave a Reply