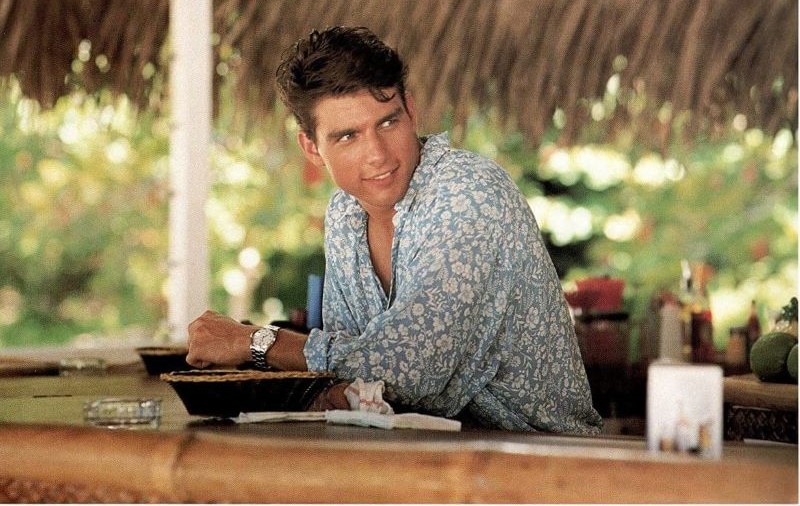

After film “Cocktail” starring Tom Cruise test screened before release, studio executives and talent were puzzled that audience felt it saw two films … and didn’t like the second one.

The initial two-thirds of the 1998 movie were well-received as a light-hearted, young-adult romantic romp. Cruise is an appealing, fun-loving bartender starring in his next film after his “Top Gun” hit.

The book “Audience•ology: How Audiences Shape the Films that We Love” by researchers Kevin Goetz with Darlene Hayman then explains the rub. “In the third act of the film, a tragic turn of events occurs in which the main character’s former boss and someone who had presented conflict for him (played by Bryan Brown) dies by suicide,” recounts “Audience•ology.” “Cruise’s character discovers his body, and in that early version, the movie ends quickly thereafter.” Audiences found the downer ending jarring for an otherwise let’s-party-fun film.

Afterward, the movie underwent some reshoots and editing, adding personal subplot hurdles for the Cruise character to overcome. Further, the suicide became less central. Critics didn’t like “Cocktail” when it opened in general theatrical release, but audiences did as “Cocktail” ranked as the ninth biggest domestic grosser from 1988.

“Audience•ology” is very well written with compact text. Goetz (pronounced “gets”) is CEO and founder of Screen Engine/ASI, with 30 years in movie marketing research. Hayman is a movie marketing executive as well.

His book describes audience screenings through lively anecdotes (which can be described as “war stories”) from real-life events (mostly research that marketing guru Goetz worked directly). Each movie’s tale in research is presented through the eyes of a studio executives or talent with nicely fashioned backstory (a minority of passages don’t mention names of persons or movie titles). Most anecdotes regard familiar film titles from a decade ago or farther back.

The books recounts:

* Marketing executives beware! Talent and distribution executives will sometimes blame researchers for poor test results from the audience, which is an occupational hazard.

* The test showings are secret prerelease screenings of films in various stages of completion. Typically, the audience is 300-400 people who are recruited. Researchers know the demographic profile of each respondent, so results can be sorted by age, gender and any other known audience characteristic.

* Recruited audiences often don’t know the film being tested. For 1997 eventual blockbuster “Titanic,” a test audience in Minneapolis was told it would be seeing romantic drama “Great Expectations,” but were delighted by the switcheroo.

“A test screening is judgement time, the moment of reckoning, the moment of truth,” says “Audience•ology.” “Test screenings are a juncture where talent and Hollywood executives need to be humble and open minded because the audience is in charge briefly at that point.” For those involved in film, it’s the climax of a long slog of work on a single project that will impact their livelihood going forward. A hit film opens the door for talent’s next job.

Some creative talent are dismissive of audience test screenings of movies, but “Audience•ology” points out that audience testing sometimes “saves” films, such as “Paranormal Activity.” That shoe-string budget film from 2007 was going to go direct-to-video, skipping cinemas. But results from a Glendale, Calif., screening rated the horror suspense flick as cinema-ready with a little tweaking.

The favorable test result showed that “Paranormal Activity” wasn’t just “another found footage movie with a shaky camera that makes everyone in the theater nauseated,” says the book. At around the the same time, adventure sci-fi horror film “Cloverfield” had a similar profile. Another movie that got elevated distribution because of unexpectedly high test-audience response is 1989 light social drama “Driving Miss Daisy.” It went on to win Best Picture at the Oscars.

For creative talent disdainful of pre-release audience testing, research guru Goetz counters getting an outside opinion is always helpful and worth study.

”My advice to filmmakers when their films test really poorly is to look beyond the numbers and read the cards,” says the book. The “cards” are questionnaire that test audiences fill out after seeing a movie.

“There are always insights to be gleaned from the comments that moviegoers write,” says “Audience•ology”. “Copies of the surveys are available to them, posted to a secure site for downloading, or delivered digitally to them on the night of the screening or the morning after.”

Related content:

Leave a Reply