A little-understood aspect of cinema booking contracts is that a larger percentage of boxoffice revenue is allocated to the Hollywood major studios as a blockbuster film climbs into the stratosphere. The result is that the financial benefits of outsized hits disproportionately go into the pockets of major-studio distributors, and less so to theaters.

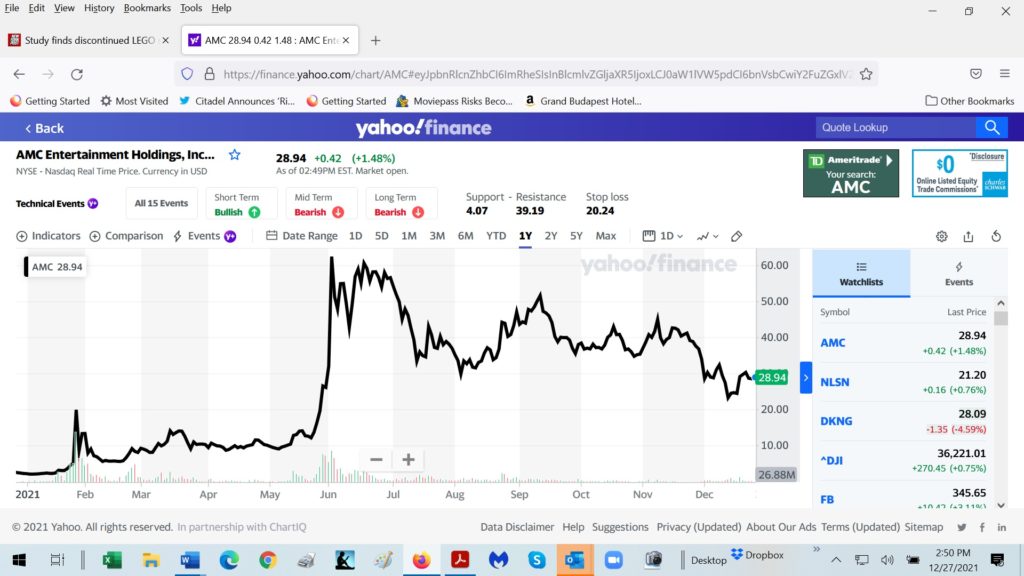

Hey all you “meme” small investors who bid up stock of cinema chain AMC Theatres. … Do you realize that divvying up boxoffice — which in cinema parlance is distributors collecting “film rentals” — is not a straight-line affair? The memes are small investors who also call themselves “apes” and move as a pack, driven by chat-board posts.

Most recently, the good news energizing memes was “Spider-Man: No Way Home” that premiered to a mind-boggling $260.1 million domestically for its Dec. 17-19 premiere weekend.

For the industry as a whole, MarketingMovies.net estimates that the swing in rental — again distributors’ cut of boxoffice dollars — is a dozen percentage points, ranging between 50-62% for each boxoffice dollar (explained in more detail further down). The main beneficiaries are Hollywood’s handful of major movie studios.

Financial disclosures of publicly traded cinema circuits confirm directionally this tilt-to-Hollywood characteristic of the industry booking contracts. The 10K disclosure statement of third-ranked U.S. theater chain Cinemark states: “Film rental costs as a percentage of revenues [an expense for Cinemark] are generally higher for periods in which more blockbuster films are released,” which acknowledges distributors get an outsized cut when “more blockbusters” are in theaters. Canadian theater giant Cineplex states in its 2020 disclosure that “stronger performing films having a higher film cost percentage.”

Film Rentals Percentage Increases for Hit Films

Boxoffice@Rental Percent=Absolute Dollars

* $110m @ 52.5% = $57.75m leaving for cinemas $52.25m

* $105m @ 52.5% = $55.1m leaving for cinemas $49.9m

* $95m @48% = $45.6m leaving for cinemas $49.4m

* $80m @ 48% = $38.4m leaving for cinemas $41.6m

Note: This example is relevant for normal, non-pandemic environment. Assumes no parallel video streaming with cinema release. Percentage for film rentals (an expense to theaters) jumps to 52.5% at $105 million in domestic boxoffice, from 48% if the film reaches that level.

While confirming directionally, the theater circuits don’t provide much in the way of granular detail. In fact, the expense of paying Hollywood rentals is muddled in financial reporting of publicy traded movie theaters by combining with theater advertising. Cinema advertising expense is minuscule, because Hollywood film distributors pay for most of theatrical advertising, but combining with film rentals shrouds the exact expense of rentals paid to film distributors.

Cinemark disclosure filings again provide a little more specific insight, noting film rentals (payments to Hollywood distributors) coupled with that very small advertising expense were 53.3% of each boxoffice dollar in the covid-impacted year of 2020, but nearly 4 percentage points higher in the prior year loaded with more blockbuster films. “Film rentals and advertising costs were 57.2% of admissions revenues for 2019, which reflected a higher concentration of blockbuster films,” says Cinemark.

Macquarie Research USA, an arm of the global investment giant, illuminated this economic nugget in a comprehensive 2016 report about cinema. Macquarie estimated films grossing under $50 million domestically split each boxoffice dollar 50/50 between distributors and cinemas, so the distributor got a 50% rental. Films grossing $200-250 million generated a 56% rental to film distributors (whittling down cinemas’ take to 44%). For films hitting $500 million, distributors took 62% rentals (leaving cinemas with 38%).

This formula is so little known it doesn’t have a commonly accepted name across industry. Some refer to it as “pay for performance” or “sliding scale.” It’s also misunderstood because the financial press might cite a 60% rental, without explaining that lofty cut of boxoffice is just for one blockbuster film.

Despite paying a higher percentage of boxoffice for big hits, theaters do okay. Retaining a lowly 38% from a $500 million grossing film is still $190 million to cinemas; 44% of a $200 million grossing film leaves $88 million, while a high 50% cut of boxoffice of a $50 million film is just $25 million.

Writes Anthony D’Alessandro in Deadline.com for an estimate of profitability for “Spider-Man: No Way Home,” “After exhibition’s cut of the box office, global rentals will send $825M back to Sony.” That’s from theaters worldwide; typically the rentals percentage overseas is lower than domestically. Deadline is estimating $1.75 billion in worldwide boxoffice, of which $750 million comes from domestic.

MarketingMovies.net provides some context. “The word ‘rental’ is used because theaters contract for limited rights to the movies they screen,” notes the third edition of the book “Marketing to Moviegoers.”

And not every Hollywood distributor gets stratospheric rentals. Only Hollywood’s major studios have the clout to negotiate outsized rentals well above 50% — they are Walt Disney Studios, Sony Pictures, Paramount Pictures, Universal Pictures and Warner Bros. Pictures. Since those five majors account for 80-85% of domestic boxoffice in a normalized year, they skew the overall industry average.

The remaining boxoffice (15-20% of domestic ticket dollars) is held by independent distributors and the indie-arms of the majors. Their rentals are closer to 50% (and for some individual indie movies even less than 50%). But the overall domestic market average is still around 55% because the five majors account for the lion’s share of business.

And this whole discussion is the “domestic” market — United States and Canada, which for the purposes of theatrical distribution are bundled together as a single unit. And when movies play in streaming while in cinemas, the standard booking template is subject to changes benefiting cinemas.

Why do Hollywood distributors merit a bigger slice of hit films? The rationale is that theaters have their overhead covered with the initial wave of attendance, cinemas don’t pay the up to $60 million in domestic marketing costs to support a theatrical release (distributors shoulder marketing costs), the Hollywood distributors cover all of the production cost (that can be $200 million for some movies) and cinemas do keep all the high-profit food/beverage money.

Years ago, a more complex scaled formula was used to divvy up boxoffice, with one element at the extreme 90-10 split favoring Hollywood distributors — in some instances. However, that 90-10 was only half the formula; the other half benefited cinemas alone, so the net was closer to an even split.

The discussion of the modern formula for splitting boxoffice can be generalized in broad strokes, but actual contracts may have tweaks of differentiation. Those differences can be due to historical deal terms between a theater and a distributor, and also competitive position of any given theater location (does the exhibition zone/district have three theaters or one? … If it’s one, then that theater has more negotiating clout). Another tweak is whether film supply is expected to be plentiful or thin during a movie’s run. “From an exhibitor’s perspective, a marketplace that is crowded with high-grossing films is good not only for the high revenue generated from films then playing but also because crowded screens give exhibitors negotiating clout in future bookings, as distributors find it difficult to secure play dates,” says “Marketing to Moviegoers.”

It’s a fact of life that cinemas get proportionally less on a percent basis of big hits and this is baked into longstanding industry economics. Projecting cinema rentals on a straight-line percentage midjudges the economics.

Related content:

Leave a Reply