The digital native atop Hollywood’s largest major studio gave a full endorsement to cinema release, as the broader rebound of the theatrical film business takes shape post-pandemic.

Jason Kilar, head of mammoth Hollywood enterprise WarnerMedia, told a recent MoffettNathanson investors’ conference: “You should expect us to lean into theatrical distribution for decades and decades to come. I think that’s a great experience.” He explained that consumers get fed up by watching all their movies at home or on their portable devices; they want an occasional night out at the cinema.

Kilar, whose purview includes Warner Bros. Pictures, is a 50-year-old digital validator because he came from pioneering video streamers Hulu (now controlled by Walt Disney Co.)

This year Warner Bros. movies will premiere simultaneous on HBO Max, the streamer owned by Warner Media. But Kilar says that a cinema-to-streaming spacing will return for Warner films in 2022. He said that big films could in theaters 45 days in theaters before coming to HBO Max.

Presumably, other movies could have shorter windows or even debut on a streaming service and in theaters simultaneously. Kilar arrived two years ago, and overhauled strategy and executive ranks.

Windows are shortening because in 2019 prior to pandemic disruptions, cinemas had a 90-day exclusive window before streaming/home video. Early indications are that shorter windows will work.

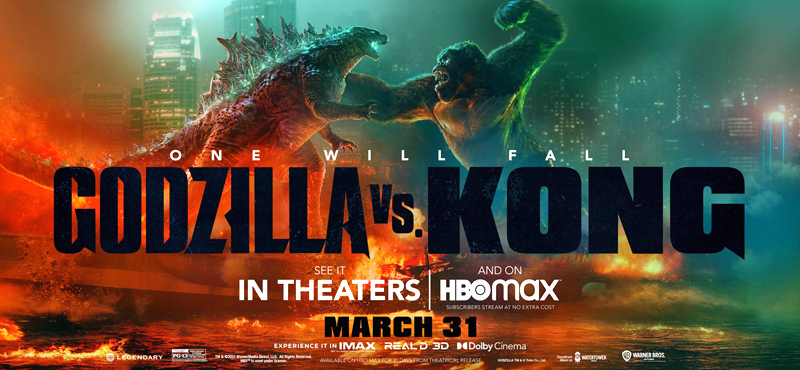

Warner Bros. “Godzilla vs. Kong” sci-fi monster movie grossed a blockbuster $31.6 million in its opening weekend while also being on HBO Max. Since its March 31 premiere on both HBO Cinemax and theaters, the PG-13 “Godzilla vs. Kong” has rolled up $95 million in domestic boxoffice (U.S./Canada) and $427.1 million globally (all territories including domestic). That is very good given some cinemas are not yet open due to the Corona-19 virus.

Understanding streaming windows for new films is complicated because now three distinct configurations have emerged. The most common is unlimited consumption for a flat fee, such as all Netflix content in video-on-demand (VOD) for $8.99 (basic) a month with no advertising (see table below). Then there’s the premium-VOD (P-VOD) where one title is $20-40 for 48-hour rental — consumer take-up is limited because of that extra charge. The third is emerging quickly — advertising VOD (also known as FAST-free ad-supported television) where streaming carries ads and the A-VOD is either free or reduced price.

P-VOD windows, because they carry a high price point, are a low-level threat to cinema even though they are typically stacked up adjacent to theatrical release.

Clearly there is a collaboration between movie companies and exhibition — the cinema sector. Third-ranked cinema chain Cinemark concluded deals last month with all five of Hollywood’s major studios carving out an early streaming window. This mean streaming original movies like Netflix’s “Army of the Dead” get decent cinema runs.

There is customization for release patterns for streaming original movies. For big films that linger in theaters, it’s believed a centerpiece of the Cinemark accord is 31-day exclusive cinema window — that’s five weekends, which are the peak moviegoing days. Smaller films linger in theaters shorter times and the streaming window is presumably sooner.

Cinemas are reopening now after the pandemic and early business is encouraging, as consumers cooped up seem eager to resume out-of-home experiences. Some theater chains are suffering financially, but even if they become insolvent a new owner would likely step in. Indeed, with regular stores closing amid consumer buying shifts to mail order, there is no demand for vacant retail space, especially special-purpose cinema layouts.

Suffering from high vacancy rates, physical shopping malls are stretching to keep renting to movie theaters and stores. For example, two large shopping malls jointly bought once-giant department-store retailer JCPenney out of bankruptcy simply to keep their properties occupied.

Hollywood major studios can be forgiven for favoring corporate sibling streamers with fast windows around cinema, because riches and survival in the streaming age are at stake. A stock analyst estimated suggested that Disney+ was worth a staggering $100 billion just two months after its successful launch. Streamers are “scalable” meaning they easily can go global and adding subscribers is not expensive once initially set up.

For HBO Max, it is part of debt-heavy telecom giant AT&T that was burned by buying satellite TV DirecTV in 2015 at what was the end of the cable TV boom. So, AT&T’s hopes for comeback and to generate cash to pay off debt rests with HBO Max succeeding as a streamer. As this article was posted, Jason Kilar’s world got rocked with the announcement AT&T is selling WarnerMedia (Warner Bros. HBO, a stake in DirecTV, CNN and other media assets) to reality-TV channel Discovery Inc., and the Discovery chief will run the business post-merger.

In his presentation to analysts, Kilar pointed out Hollywood’s major studios like Warner Bros. are not “a one-trick pony,” as many detractors suggest, because of their cinema connection. (Indeed, it’s the pure streamers are one-trick ponies because of their small footprints in cinema).

“We have theatrical,” Kilar says. “And, by the way, theatrical is not just a distribution strategy or even just a business model. In many ways, it positions a story in the mind of a consumer unlike anything else.” All those theater marquees trumpeting movie titles to consumers, good financial returns from hit theatrical play, cinema awards and film critics obsessed with film point to Hollywood sticking with cinema.

Related content:

Leave a Reply