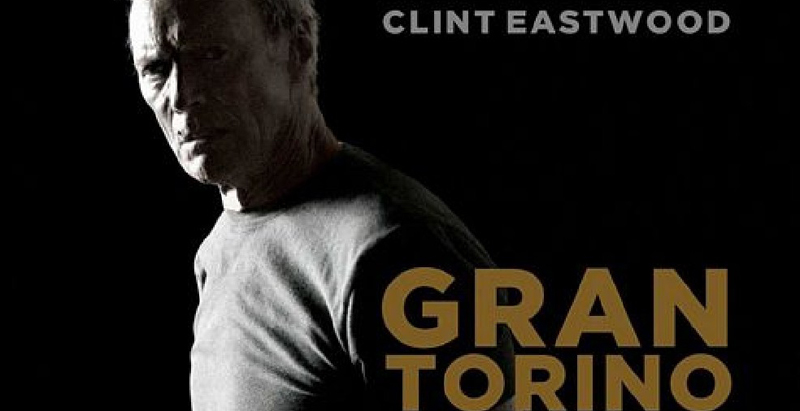

The one-sheet movie posters certainly seem promising. There’s the close-up, tender embrace of Kate Winslet and Leonardo DiCaprio that calls to mind their “Titanic” pairing. Separately, Clint Eastwood strikes a steely “Dirty Harry”-esqe pose grimacing with a hard-ass facial expression.

Trouble is…the advertising doesn’t truly represent the films involved.

Winslet and DiCaprio strike a loving pose in sour marriage drama “Revolutionary Road” that “ends unhappily, with a gruesome death, and neither of the main characters is entirely likable to begin with,” notes a “New York Times” review. The review is headlined “Kate! Leo! Gloom! Doom! Can It Work?”

Warner Bros. Pictures probably wouldn’t object if ads remind fans of Eastwood’s heroic action dramas of the past. But “Gran Torino” examines white racism and blue-collar bigotry against a backdrop of urban decay and ethnic friction in contemporary America. “New York Post” columnist Kyle Smith laments of Eastwood “now his movies are all about how complicated it is to figure out who has the moral high ground.”

Since it’s hard to convince moviegoers to part with $10.50 for a silver screen oozing with marital anger and moral ambiguity, the movie posters pitch love, the gun and the tough-guy.

How does this end up happening? Several factors are at play.

Sometimes, it’s a case of Hollywood stars taking the “one for them and one for me” approach to their careers. That is, talent will do one studio films with mainstream appeal for fat paychecks, and then every other film is a passion project with serious and often depressing subject matter. The weighty movies win awards and impress peers in Hollywood.

But the distributors of the passion projects often employ ads that play off star power, and downplay or ignore aspects of the film that are un-commercial. As “Entertainment Weekly” noted in two passages when writing up a “The Lucky Ones,” which is drama about returning soldiers from the Iraq War, “The word ‘Iraq’ is never mentioned.”

In other instances, films don’t turn out the way that studios plan because filmmakers veer off course, either by accident or perhaps by design when studio brass isn’t watching.

A passage in the second edition of book “Marketing to Moviegoers” notes that studio executive Chris McGurk said when testifying before a U. S. Senate hearing in 2000 that was critical of film marketing practices: “Completed motion pictures sometimes do not exactly conform with the type of film the studio believed it was making when it originally green lit [approved] the project. In addition, completed pictures often appeal to an audience different from the one that they were originally supposed to reach.”

Perhaps the most likely reason for disconnect between films and their ads is that movie campaigns are extensively pre-tested for effectiveness. After side-by-side test comparisons of either true-to-the-downer-movie or just-sell-the-famous-actor, it’s the Hollywood gloss that usually rates higher and gets blasted across the marketplace.

Probably the best example of films pursuing an obviously non-commercial track is the recent spate of serious films that are critical of U.S. involvement in Afghanistan, Iraq and Middle East. These include “Redacted”, “Rendition”, “Body of Lies”, “In the Valley of Elah”, “The Kingdom”, “Grace Is Gone”, “A Mighty Heart”, “Taxi to the Dark Side”, “The Lucky Ones and “Lions for Lambs”—all of which were box office disappointments to varying degrees.

In “Body of Lies” and “The Kingdom,” America’s covert warriors are immoral and America has no friends overseas. In its year-end box office report last year, a “USA Today” article observed, “Look at the lowest-grossing movies of the year, and they are littered with stories with something political to say.”

Advertising for most of these films kept out the topical themes to instead emphasize star power (Tommy Lee Jones for “In the Valley of Elah”) or thriller genres without mention of the Middle East backdrop. Even satires were tough sells as right-leaning “An American Carol” and left-leaning “War Inc.” both bombed. However, the black comedy “Burn After Reading” grossed a solid $60.3 million domestically.

Films from independent distributors have long emphasized weighty themes, and what’s new is that major studios have decided to tackle uphill topics. “The Kingdom” is an $80 million production that grossed a disappointing $47.5 million domestically. The $70 million production of “Body of Lies” did even worse with $39.4 million domestically. However, some succeed as Eastwood’s “Grand Torino” is an emerging blockbuster.

The vein of serious Middle East war/terrorism films has petered out so perhaps it is slowly dawning on Hollywood that a political orientation does not correlate to impressive box office. Of course, there are exceptions, especially Iraq war blockbuster documentary “Fahrenheit 9/11.”

This critique is not a call to banish serious topics or politics, but rather to remind that movies are in show business and let’s not forget that “business” part. Indies are low rollers that can get a decent economic return on a niche film if it connects with its desired audience segment. A moderate budget for a serious film is a reasonable bet bet. But big expensive films need to connect with broad, mainstream audiences to be financial successes.

With tens of millions of dollars at risk, the movie business is not analogous to a high-minded artist painter working alone with a simple canvass and paints to satisfy a creative inspiration. Further, film companies have pleaded poverty recently as they cut staff headcount recently and so there’s a human suffering consequence to not being attuned to the audience and box office.

Hollywood’s economy would be better off if films that it makes fit the ad campaigns and this would have the extra dividend of being honest with moviegoers (hey, there’s a novel concept!). Financial risks should not be shrugged off by an implied willingness to resort to a marketing campaign that is cynically not true to movie.

Related content:

Leave a Reply